Table 1: A Chronological Compendium of Key Milestones in Nanotechnology

Year | Milestone/Discovery | Key Figures/Institution | Significance |

4th Century | Lycurgus Cup | Roman artisans | Unintentional creation of dichroic glass using gold and silver nanoparticles, demonstrating size-dependent optical effects [1]. |

1857 | Colloidal Gold Experiments | Michael Faraday | First scientific recognition that the optical properties (e.g., color) of a material can change at the nanoscale [2]. |

1931 | Invention of Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll | Enabled the first direct visualization of nanoscale structures, becoming a critical tool for characterizing nanomaterials [2]. |

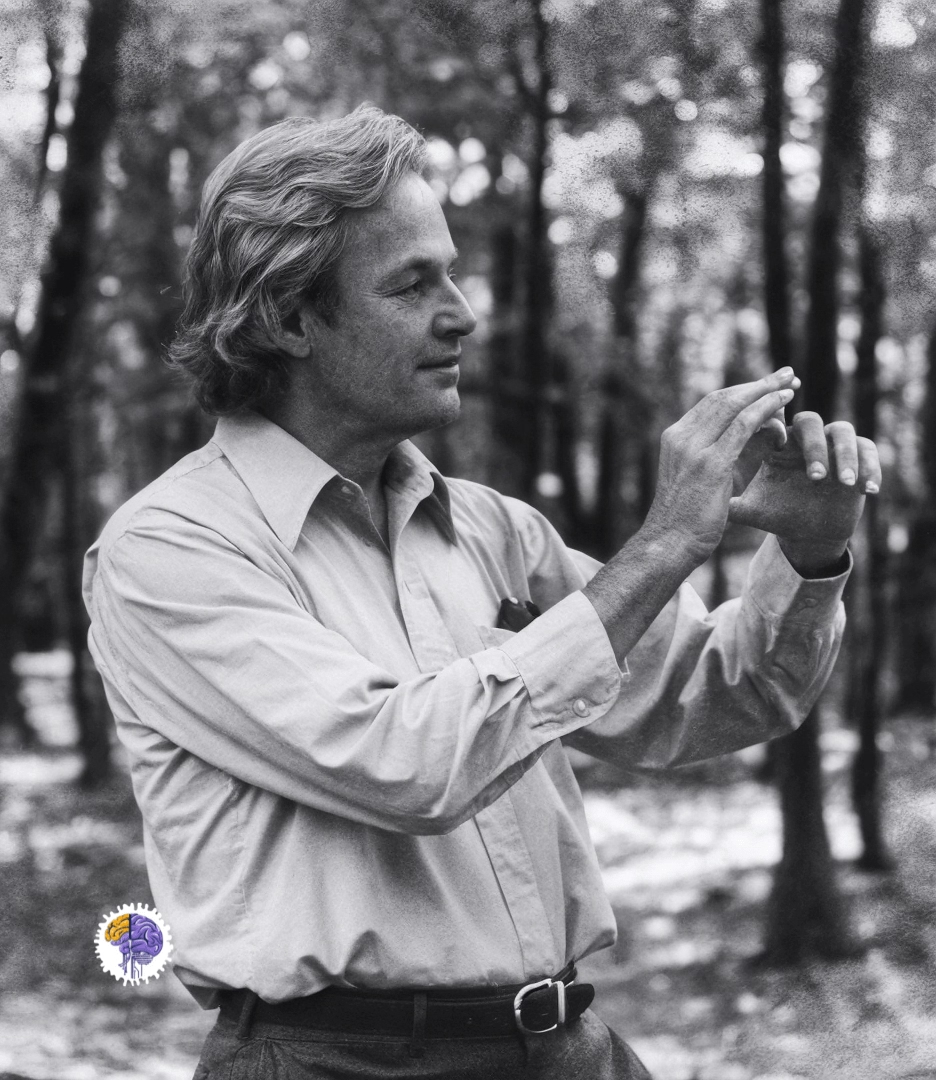

1959 | “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom” Lecture | Richard Feynman (Caltech) | Provided the visionary, theoretical foundation for nanotechnology, proposing the direct manipulation of individual atoms [2]. |

1974 | Coining of the Term “Nano-technology” | Norio Taniguchi (Tokyo University of Science) | First use of the term to describe precision engineering and manufacturing at the nanometer scale [2]. |

1981 | Invention of Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM) | Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer (IBM Zurich) | Revolutionary invention that allowed for the imaging and, later, manipulation of individual atoms on a surface [2]. |

1985 | Discovery of Fullerenes (Buckyballs) | Robert Curl, Harold Kroto, and Richard Smalley (Rice University) | Discovery of C60, a new spherical allotrope of carbon, which opened the field of fullerene chemistry and carbon nanomaterials [2]. |

1986 | Invention of Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | Gerd Binnig, Calvin Quate, and Christoph Gerber (IBM/Stanford) | Expanded scanning probe microscopy to non-conductive materials, including biological samples, democratizing nanoscale imaging [2]. |

1986 | Publication of Engines of Creation | K. Eric Drexler | Popularized the concept of molecular nanotechnology, introducing ideas like assemblers and the “grey goo” scenario to the public [3]. |

1989 | First Manipulation of Individual Atoms | Donald Eigler and Erhard Schweizer (IBM Almaden) | Used an STM to spell “IBM” with 35 xenon atoms, providing definitive proof of Feynman’s vision of atomic manipulation [2]. |

1991 | Discovery of Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Sumio Iijima (NEC Corporation) | Discovery of tubular carbon structures with extraordinary mechanical and electrical properties, becoming a cornerstone of nanotechnology [2]. |

2000 | Launch of the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI) | U.S. Government | A major federal research program that coordinated and funded nanotechnology research, accelerating its development globally [2]. |

2004 | Isolation of Graphene | Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov (University of Manchester) | Isolation of a single, one-atom-thick sheet of carbon, a 2D material with unprecedented properties, sparking a new wave of research [2]. |

1. Is nanotechnology a completely modern invention?

2. How is the Lycurgus Cup an example of ancient nanotechnology?

3. What gives medieval stained glass its brilliant colors?

4. What made the legendary Damascus steel blades so strong?

5. Who first gave the visionary idea for modern nanotechnology?

6. Who actually coined the term "nano-technology"?

7. What was K. Eric Drexler's contribution to the field?

8. What is the "grey goo" scenario?

9. What inventions were critical to seeing and manipulating the nanoscale?

[1]. Nanotechnology Timeline, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://www.nano.gov/timeline/

[2]. 1.2 Historical Development and Milestones in Nanotechnology – Fiveable, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://fiveable.me/introduction-nanotechnology/unit-1/historical-development-milestones-nanotechnology/study-guide/U28ogmx53wvhvFfT

[3]. From Faraday to nanotubes – timeline — Science Learning Hub, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/1658-from-faraday-to-nanotubes-timeline

[4]. History of nanotechnology – Wikipedia, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_nanotechnology

[5]. History of Nanotechnology – Ossila, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://www.ossila.com/pages/history-of-nanotechnology

[6]. Nobel Prize in the field of nanotechnology – MolecularCloud, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://www.molecularcloud.org/p/nobel-prize-in-the-field-of-nanotechnology

[7]. Introduction, history and Timeline of Nanobiotechnology – Nptel, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://archive.nptel.ac.in/content/storage2/courses/118107015/module1/lecture1/lecture1.pdf

[8]. There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom – Wikipedia, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/There%27s_Plenty_of_Room_at_the_Bottom

[9]. Plenty of Room at the Bottom – Richard P. Feynman, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://web.pa.msu.edu/people/yang/RFeynman_plentySpace.pdf

[10]. Risk Management Magazine – Nanotech’s Troubled Past, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://www.rmmagazine.com/articles/article/2013/04/09/-Nanotech-s-Troubled-Past-

[11]. Norio Taniguchi – Wikipedia, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norio_Taniguchi

[12]. There is plenty of room for practical innovation at the nanoscale. But first, scientists have to understand the unique physics t – ROUKES GROUP, accessed on September 25, 2025, http://nano.caltech.edu/publications/papers/SciAm-Sep01.pdf

[13]. Richard Feynman, 1984. Photo by [Tamiko Thiel]. Source: [Wikimedia Commons]. Licensed under [CC BY-SA 3.0].

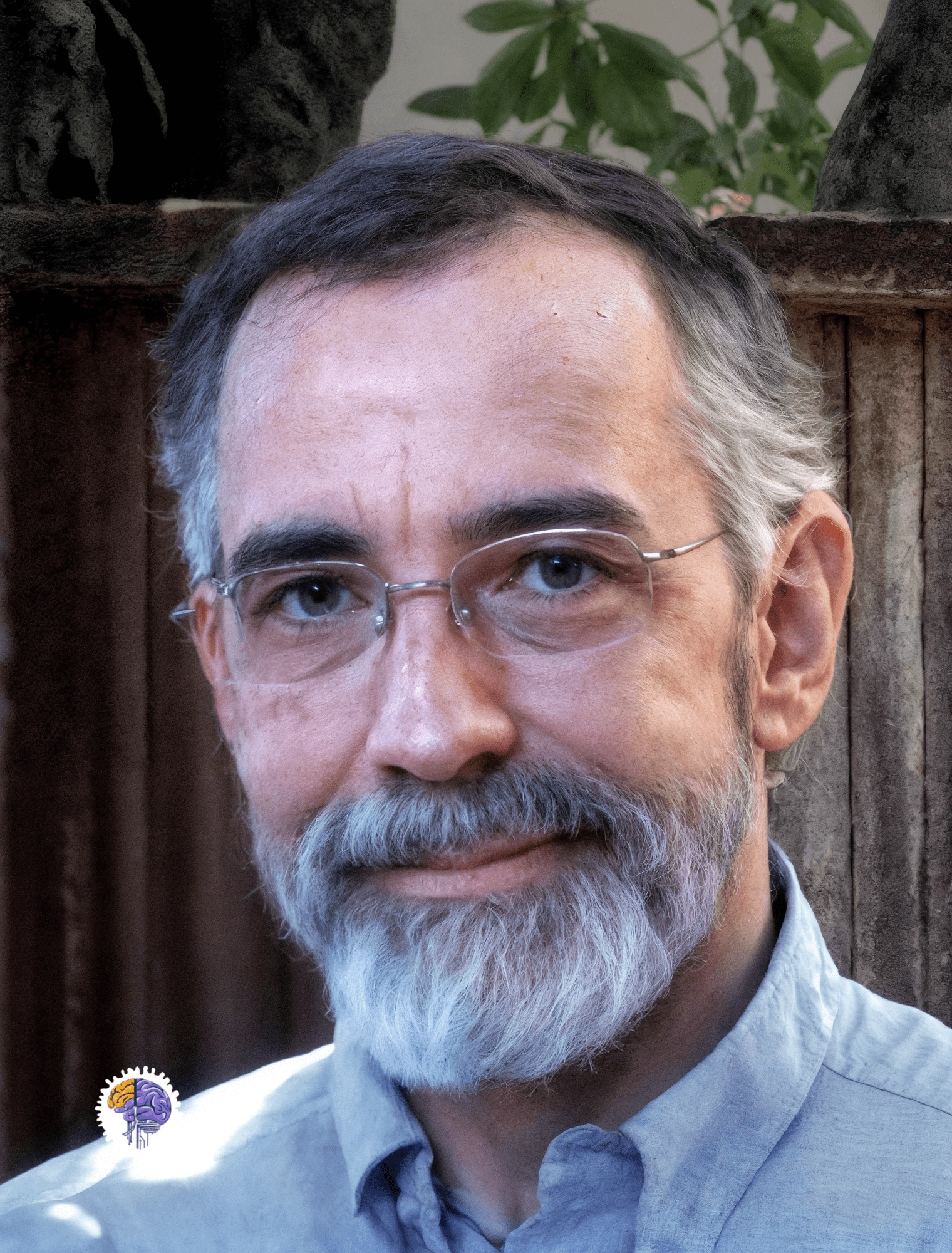

[14]. Dr. K. Eric Drexler, 2013. Photo by [Eric Drexler]. Source: [Wikimedia Commons]. Licensed under [CC BY-SA 3.0].